Predicting 2050: Because next year is too soon to be proved wrong

To imagine the newsroom of mid-century, start in the year 2000 when phones couldn’t quite stream video and newspapers still sold millions. The clues to journalism’s future are already with us.

December is traditionally the month of media predictions for the next 12 months. Who will be defenestrated from political life? What will people be wearing on the beach next summer? And in my field, how will news change next year? Every year, the Nieman lab publishes its predictions, and while some of them are sharp, they usually contain more questionable claims, like this is the year that local news succeeds, that the battle over journalism’s ethics and practices is finally won, and that we are all finally converted to vertical video.

The trouble for sages who predict seismic change in just a few weeks or months is that everyone can check whether they were right. And change is often a process that takes longer than early adopters tend to think. So, inspired by a CJR article looking at the same idea, I thought I’d give myself a long enough lead time to avoid being proved quickly wrong and to see the tectonic plates move.

As all good sci-fi writers know, to write about the future, you need to start by looking at the past. To imagine how the news of 2050 might look, let’s consider the news of the year 2000 and how it compares with today.

Back in the year 2000, broadcasting and newspapers were still the main ways in which people got their news. The main bulletins on the public service broadcasters, BBC, ITV, Channels 4 and 5, had been joined by rolling news with the emergence of satellite, cable and digital television – Sky News in 1989, BBC News 24 in 1997, and the ITN News Channel in 2000. Radio too had increased its news coverage with BBC 5 Live relaunching as a news and sport station in 1994. Newspapers still luxuriated in sales running into millions – The Sun selling more than 3.5 million copies a day, even the broadsheet Daily Telegraph could shift more than a million copies per edition – today it barely sells 150,000 a day.

And yet from the perspective of 2025, one can already see that they were already in long-term decline. Audiences and circulations were tumbling; digital editions had been launched that would move centre stage in the following decades. The long-term decline in audience trust and willingness to pay for news was already underway.

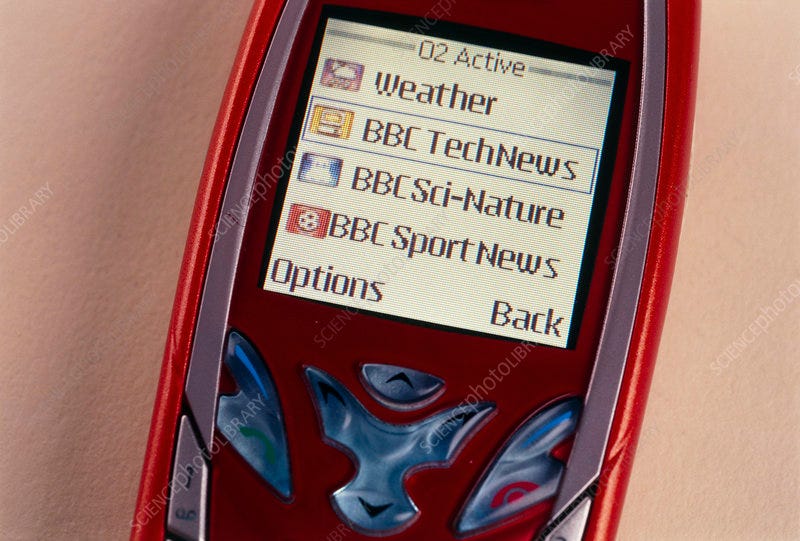

There’s a perceptive quote – usually attributed to Neuromancer author, William Gibson, “The future is already here - it’s just unevenly distributed”. In late 2000, I joined the newly launched ITN News Channel as a producer. It was late to the market as a 24-hour news channel and only lasted until 2005 before the plug was pulled. But forward-thinking ITN executives had already spotted the possibility of delivering news headlines to internet-connected phones. In theory, the channel could even be streamed to a WAP-enabled phone. Whether anyone actually did this in practice is another matter – but the idea of delivering news to a digitally connected phone was, as we now know, the future of news. It had already arrived, even if not evenly distributed.

So, what does the state of the media in 2000 tell us about what we might see in 2050?

In 2000, news to phones was an extraordinary technology that did not quite work, today it’s the way in which most of us discover news, in 2050 it will be the past. My suspicion is that wearable digital devices point to the future. While the current crop of AR-enabled glasses is pretty clunky, 25 years of refinement and the incorporation of increasingly sophisticated AI may leave us with wearable devices that will be able to deliver personalised news and information on command. It may not be quite the dream of Captain Picard’s badge communicator, but it may not be far removed from it.

Artificial intelligence is the latest trend to explode across the media. This one is set to stay the course, just as websites did in 2000, and by 2050, its use in the production and delivery of media will be everywhere. The ethical concerns that have slowed its uptake in news won’t have completely disappeared, but the guardrails that will be established in the next few years will mean AI video won’t be used deceptively, but it will be used to explain stories in a stylised manner – like this Netflix explainer. AI won’t be doing on-the-ground newsgathering. But its use in OSINT, parsing public data, and creating personalised stories will be routine.

Of course, comparing today to 25 years ago also reminds us how slowly some things change too. The BBC is still here; most of the national newspapers are still here; we still go to the cinema, the football, the theatre, and the opera. Media formats can be much stickier than people imagine. When I was working for The Times in 2008, News International established a new £350m printing facility in Broxbourne to be paid for over 25 years. Those of us working on the website were incredulous that Rupert Murdoch was throwing away his money, given that newspapers were certain to be obsolete within a couple of years. 17 years later, the presses are still rolling, even if printing fewer daily copies.

By 2050, I think we can be certain that newspapers will finally be digital-only. But the main national brands, The Times, The Telegraph, and The Mail, will continue. They might be shadows of their former selves – after all, they already are – but they will still be a source of news for many readers. The BBC too will still be with us. 25 years from now, its charter will have been renewed twice more after a deal is completed next year. I do think the Licence Fee will have gone by then, but probably only just. It will definitely remain in 2027; it may well continue after 2037, although I think some of the arguments about universal access will become more difficult to make at this point. By 2047, the BBC will deliver some form of personalised public service media direct to consumers as the old linear channel, BBC1, is finally phased out. Radio too will continue. 25 years is far too soon to see the end of BBC Radio 3 or 4. I suspect people will still be starting the day with the Today programme at the end of century.

So, some predictions for how news might change and how it might remain similar by mid-century. Please do check back in 25 years to see whether I was anywhere close to being right.